Trying out Zig - Zigominoes

Contents

Over the last year or so I’ve been tempted to learn Rust as a more modern alternative to C or C++. I did have a go at learning it, but I found myself fighting with it more than I’d hoped. So I decided to try out Zig instead!

What is Zig?

Zig is a quite/very new language depending on how you look at it - it’s been around since early 2016, so it’s newer than Rust and Go, which appeared around 2010. Zig is still in beta (I’m using 0.7.1), but the creator, Andrew Kelley, is working on it full time, and I get the impression release 1.0.0 is somewhere on the horizon. The original blog post introducing the language can be found at https://andrewkelley.me/post/intro-to-zig.html.

I’d recommend checking out the homepage: https://ziglang.org/, which lists the ‘feature highlights’ of the language. For those that prefer to stay here, the list of features that appeal most to me are below.

- Small, simple language (easy to learn)

- Performance and safety (safer alternative to C/C++)

- Optional type instead of null pointers

- Built-in clean error handling

- Compile-time code execution

- Built-in code formatter (‘

zig fmt’) - Native FFI with C

- Provides async without function colouring

- I find the syntax clean and easy to read on the whole (despite it not being finalised yet)

My Toy Project

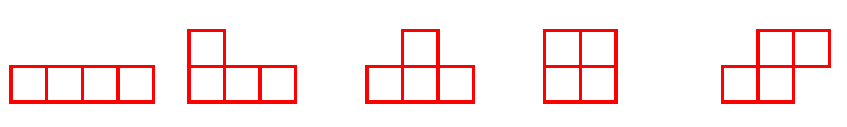

As a fun little project to try out the language, I decided to try reimplementing my first ever computer program! The purpose of the program is to find the n-ominoes for n = 1, 2, 3, …, for example ‘dominoes’ are 2-ominoes and ‘tetrominoes’ (tetris shapes) are 4-ominoes. To illustrate the intent, the five unique 4-ominoes are shown below:

This is an interesting problem because it has a verifiable result, and performance matters (the number of ominoes grows exponentially with n). Originally it was Python 2, mostly written by my stepdad while I watched and absorbed as much as I could.

I ported the original code to Python 3 and uploaded to GitHub, which you can find at https://github.com/LewisGaul/pyominoes.

My Zig code can be found at https://github.com/LewisGaul/zigominoes, although at the time of writing it fails when it gets to something like 8-ominoes - I need to look into this.

Getting Set Up

Following instructions at https://ziglang.org/download/, I first tried downloading Zig using apt on Ubuntu. However, I ended up with version 0.6, which I wasn’t satisfied with.

Instead, I just downloaded the zig-linux-x86_64-0.7.1.tar.xz archive, unpacked it, and symlinked the zig-linux-x86_64-0.7.1/zig executable to a location on PATH (~/bin/ in my case). This was no-fuss, and works just fine.

I use PyCharm as my IDE whenever possible, but unsurprisingly there’s no Zig support (yet). Instead I fell back to VSCode, where I was able to get a good setup without much difficulty.

First I installed the main Zig extension. I then set up ZLS (the Zig Language Server) for code tagging (being able to jump to definition in the standard library is great!). To do this I downloaded zls from releases under https://github.com/zigtools/zls (unpacking the archive and adding to PATH as for zig) and installed the ZLS extension.

Zig Details

I thought I’d go through some of the gotchas I encountered when starting out with Zig in case they help anyone else wanting to pick up the language.

The Zig language reference is a useful starting point, but it’s not yet fully complete. There’s also some standard library documentation, although the auto-generation tool used to create it appears to be very much in beta. In general I favoured looking in the Zig source (using ‘jump to definition’), which serves as a good example for how to write idiomatic Zig code.

On the other hand, there are plenty of ways to ask for help (see https://github.com/ziglang/zig/wiki/Community), and I’m sure the Zig community would be keen to have more people trying things out. Personally, I spoke to a few people on the Discord server and got some useful discussion and insights - would recommend!

Functions

For an introduction to functions in Zig see the language reference: https://ziglang.org/documentation/0.7.1/#Functions.

One of the things that initially confused me about functions in Zig was the ‘pass by value’ versus ‘pass by reference’ semantics. In the Pass-by-value Parameters section you will find the following:

Structs, unions, and arrays can sometimes be more efficiently passed as a reference, since a copy could be arbitrarily expensive depending on the size. When these types are passed as parameters, Zig may choose to copy and pass by value, or pass by reference, whichever way Zig decides will be faster. This is made possible, in part, by the fact that parameters are immutable.

This seemed to suggest there is no need to specify args as ‘arg: &MyType’ unless actually wanting to work with a pointer, whereas in C you might choose to pass a struct as a pointer to avoid expensive data copying.

I asked about this on Discord and it was pointed out to me that you must also pass by reference whenever you need to mutate, otherwise the above Zig semantics would make it unclear whether the passed-in struct was being modified or whether a copy had been taken (but don’t worry, this would be a compile error!).

Outside of those reasons, the best choice is to pass by value - Zig will take care of optimisation, and you will know the passed-in value cannot be mutated.

Another nice thing about Zig functions is that they’re first class values that can be passed around or stored as function pointers.

Optionals and Pointers

The basic syntax for working with pointers is mostly the same as C. The main difference is dereferencing pointers: ‘my_ptr.*’, which looks odd at first! This feels a bit more natural when you release ‘optional’ unpacking is similar: ‘my_optional.?’, which could be compared to a method call.

fn doubleInt(value: *u8) u8 {

return 2 * value.*;

}

test "pointers" {

var my_int: u8 = 42;

var my_int_p: *u8 = &my_int;

var result1: u8 = doubleInt(&my_int);

var result2: u8 = doubleInt(my_int_p);

std.testing.expect(result1 == 84);

std.testing.expect(result1 == result2);

}

Rather than have the concept of a null pointer, optionals and undefined are used instead. Optionals should be used to represent a value that may or may not be present (as in Rust), where null is used to denote absence of the value. The value undefined can be used to represent an uninitialised value (of any type), but will cause an error as soon as they’re used (presumably at compile time in a debug build).

fn divide(numerator: u8, denominator: u8) ?u8 {

if (denominator == 0) return null;

return numerator / denominator;

}

test "division" {

var exp_result: ?u8 = undefined; // Declare as optional u8 type

exp_result = 2; // Automatically cast to ?u8 type

std.testing.expectEqual(exp_result, divide(6, 3));

std.testing.expectEqual(

@as(?u8, null), // Explicitly cast to optional u8

divide(6, 0) // Returns null of type ?u8

);

}

Error Handling

For the most part I haven’t had to worry too much about error handling, but I still tried to do the right thing with returning errors and passing them around by prefixing the return type with ‘!’. My impression with this is that the native support for error handling is really good - mostly I’ve just used try in lots of place, but options using catch and switch look highly usable too.

Here’s an example from the documentation:

fn doAThing(str: []u8) void {

if (parseU64(str, 10)) |number| {

doSomethingWithNumber(number);

} else |err| switch (err) {

error.Overflow => {

// handle overflow...

},

// we promise that InvalidChar won't happen (or crash in debug mode if it does)

error.InvalidChar => unreachable,

}

}

Void Type

An ‘instance’ of the void type can be created using {}, which is actually just an empty block that implicitly has no value! Note that it’s possible for a block to have a value by using break, see https://ziglang.org/documentation/0.7.1/#blocks.

Alternatively you could use ‘@as(void, undefined)’, but I don’t think this is the preferred option! I guess you could be explicit with ‘const VOID = {};’ and ‘func(VOID);’ instead of ‘func({});’ (the latter looks like passing an empty array/struct to me), but I expect using {} for void is just something to get used to in Zig.

I came across the need for this in the following example:

const MyTypeSet = struct {

hash_map: ArrayHashMap(MyType, void, MyType.hash, MyType.eql, false),

pub fn sort(self: *@This()) void {

const Entry = @TypeOf(self.hash_map).Entry;

const inner = struct {

pub fn lessThan(context: void, lhs: Entry, rhs: Entry) bool {

return lhs.key.lessThan(rhs.key);

}

};

std.sort.sort(Entry, self.hash_map.items(), {}, inner.lessThan);

}

};

Note the signature for std.sort.sort(), and the fact I’m not using the context argument in my lessThan() function (showing off some of the power of reflection and comp-time execution!).

pub fn sort(

comptime T: type,

items: []T,

context: anytype,

comptime lessThan: fn (context: @TypeOf(context), lhs: T, rhs: T) bool,

) void {

...

}

Arrays, Strings and Formatting

I had some difficulty with arrays and strings early on. Now that I feel like I understand arrays and slices a bit better, I think Zig does have quite a neat implementation. However, I haven’t done a lot with raw arrays at this point.

I found a blog post, which, combined with the language reference, helped me understand how to work with strings/arrays.

From the Zig language reference docs:

Zig has no concept of strings. String literals are arrays of

u8, and in general the string type is[]u8(slice ofu8). Here we implicitly cast[5]u8to[]const u8:

const hello: []const u8 = "hello";

A slice is a pointer and a length. The difference between an array and a slice is that the array’s length is part of the type and known at compile-time, whereas the slice’s length is known at runtime. Both can be accessed with the

lenfield.

I originally tried implementing a toStr() method on a struct, and was messing around with allocating memory for a buffer and trying to work out how to do null string termination as you would in C.

I now think this is probably just the wrong approach for doing string construction in Zig, and higher level constructs should be preferred. I would suggest referring to this blog post and browsing some of the standard library code around std.io.Writer and std.fmt.format().

Final Thoughts

On the whole my impression with Zig has definitely been positive, and I have the itch to keep using it and see how it fares when used for more complex applications.

Having spent time in/around the Python, Elm and Rust communities, I have the impression that the Zig community is slightly less politics-heavy, presumably due to the fact it’s still early-stage. I could be wrong about this, I just have a good feeling about it, partly due to the level of respect I have for the creator and his approach.